by Jack E. Oliver, Copyright 2010

From the Boone County Historical Society collection. AS I REMEMBER . . . A World War II Journal by Jack E. Oliver of Columbia, Missouri. 62 pp. Available at the Boone County Historical Museum.

Mr. Oliver published these recollections of his war service in February 2010 and donated a copy of his book to the Boone County Historical Society. Included are a number of family photographs. The Society is grateful to receive this book and salutes the service of Mr. Oliver and our other veterans.

CHAPTER ONE

My Induction & Training

My Induction & Training

In January 1943, I received a notice by mail to report for my initial physical exam for military service. It was conducted at the old Noyes Hospital Building on South 6th Street in Columbia. Ahead of me in line was Harry Smith. He was an assistant football coach for Don Faurot at Mizzou, and he had been selected as the center on the all time, first 50 years All-American Football Team. It was amusing. The medical staff administering the physicals rejected this big strapping football player, and I, who weighed 136 pounds soaking wet, passed. I remember that the doctor pointed a me and said, "Now here is what we're looking for -- healthy, clear eyes, etc."

In March 1943, I received a notice, again by mail, to report to Leavenworth, Kansas for induction into the U.S. Army. About 20 other inductees and I went there by Greyhound Bus. After some preliminary concerns, we were all allowed to return home for seven days.

On Marcy 17, St. Patrick's Day, 1943, the Army directed me to return to Ft. Leavenworth. Dad took me to the bus station at 10th and Locust Streets. It was only the second time that I ever saw my dad with tears in his eyes. On the way back, the bus stopped briefly in Boonville. My brother, Harold, and his wife, Meribah, met my bus there and I was able to spend only a short time with them before heading west.

Shortly after I arrived back at Leavenworth, an orderly told my company, "Some lard-assed football player has the measles, so you guys are quarantined." The football player turned out to be Ray Evans, a famous Kansas Jayhawk player. I don't remember how long we were quarantined.

After the measles quarantine and a few more days of "hurry up and wait" preliminary processing, we all boarded a troop train. Apparently for security reasons, we were not told what our destination would be, but we traveled east. Our train rout carried us through Eldon, Missouri, where we stopped for just a few minutes. Seizing the opportunity, I gave a kid on the railroad siding a letter to my mom and a nickel. I asked him to buy a three-cent stamp and to mail it for me. He said he would, but I found out later that Mom never go the letter.

After traveling through Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Florida, and South Carolina, we finally arrived at Camp Butner, North Carolina. We were billeted in tar paper-covered barracks that had been used previously for housing Italian prisoners of war (POW's). My morale wasn't too good, and the sight of those barracks didn't help at all.

The following day we were taken to our permanent barracks and assigned to Company L, 310th Regiment, 78th Infantry Division, commanded by Major General Edwin Parker. We then embarked on a 13-week basic training period. The 78th Division was called "The Lightning Division" and we jokingly referred to ourselves as "Sparky Parker and his lightning bugs."

There was nothing difficult about our training. Over long hours we were taught close order drills, knowledge of our weapons, military bearing and discipline, how to follow orders, and how to eat our meals without getting forks in the backs of our hands. Our manners were poor at best. It was another example of survival.

After the first three weeks of training, we had a company formation. I was one of four or five in the company to get my division should patch. This qualification, which signified that I had been doing a pretty good job of adapting to Army life, was required to get a liberty pass to nearby Durham, North Carolina. I must have fooled somebody. I usually preferred to stay at camp and go to the movies on the base.

While in basic training, I found out that the Army Air Corps (predecessor to the U.S. Air Force) was taking applications for flight training. I wrote Dad and asked him to secure some letters of recommendation to accompany may application. He did this and I took my written examination in Durham. Twenty-nine enlisted men and three officers took the exam. One officer and one enlisted man scored higher than I. I though, "Man, things really look good." My bubble was soon popped, though. The medical officer found that I had flat feet, a hernia, and I couldn't balance myself on one foot with my eyes closed. I also had a perforated eardrum. I wasn't good enough for the Air corps, but plenty able to be a good dogface infantryman.

One Saturday evening I had been at the movies. When I got back to the barracks, the C.Q. (enlisted man in Charge of Quarters) came in and said, "Oliver, get your duds packed. You're going home. Our Commanding Officer, 1st Lieutenant Matico is at battalion Headquarters getting your emergency furlough papers approved."

When Lt. Matico returned to the company area, he told me that Dad was sick and that my family wanted me at home. This came as a shock, and with everything else, this really added to the stress. Lt. Matico asked me if I had any money, and I told him I didn't. He took $33.00 from company funds, mostly in dimes, and he gave it to me. There were no trains running that evening, so I had to wait until the next morning to leave. I can't recall how I got t the train station, but someone in the company must have taken me.

I took the Southern Railroad to Lynchburg, Virginia and to Cincinnati, Ohio, and I took the New York Central into St. Louis. I caught a bus from St. Louis to Columbia.

Dad was sick and was in pretty bad shape, but I was able to see him and visit with him before he died. The timing of his passing necessitated my request for a 10-day extension of my furlough, which was granted. After my time at home was up, I took a bus to St. Louis. When I arrived at the bus station, I saw a bus that had "Columbia" displayed as its destination. I already felt terrible, but seeing that was like rubbing salt in an open wound. I had to be routed to Indianapolis in order to make the proper connections. I traveled back through Lynchburg, and then back to Camp Butner.

When I got back to the Company L orderly room, Lt. Matico was there. He asked, "Well, did yo find everything well at home?" I told him then that my father had passed away. The rest of my company was out on a night problem, but Lt. Matico told me to go back to the barracks and go to bed. He had been a regular Army 1st sergeant who had received a commission. He was "strictly GI (Government Issue)," but I liked him a lot. I went on to my barracks and found Private Helfrick there. He didn't say anything, but he noticed that I was about to lose it. He said, "Damn it, Olie, just let it go." I did and I felt better.

The entire company was taking furloughs and I found out that my emergency furlough did not count against my 30-day annual leave, so after everyone else had taken their furloughs, I was given another ten days to go home. While I was home that time, I saw Robert McCown, who was also home on furlough.

Upon returning to Camp Butner, our company started the second phase of its training. I was transferred from the second platoon to the fourth, or weapons platoon, and I soon found my myself teamed up with Ora Nestor from Philippi, West Virginia. The Army apparently decided to make Nestor and me into a combat mortar crew. This was the first, and one of the few decisions that the Army made that I actually agreed with.

By this time it was early fall, and the training took us on combat maneuvers in South Carolina, and I remember that the weather was balmy there in late fall.

In February 1944 we went on maneuvers in Tennessee. The weather there was also mild, and I recall taking a bath in a small stream.

Afterward we returned to Camp Butner, and we more or less marked time until April 1944. During this time, Corporal Dodd, who was from the second platoon from which I had been transferred, asked me if I was interested in a promotion to corporal and squad leader. I suppose I didn't show enough enthusiasm, because I didn't get the promotion after all. I'm sure I was capable and could have done the job. I later learned that Corporal Dodd was killed in combat.

Had I received that promotion to corporal, I would have been assigned to a cadre that was training new recruits. Those new corporals were soon promoted to buck sergeant. As it turned out, all privates and privates first class (including me) were slated for shipment overseas.

At the end of training, we were all given 10-day furloughs. While at home, I had a conversation with my brother, Frank. We talked about how long the War would last. Although I did not remember it until Frank reminded me some time after I returned home, I forecasted that it would probably end as the result of something big. I have no idea why I said it, but it turned out that the "A" bomb was just that.

On our last night at Camp Butner, some of the guys got drunk and went a little overboard. Our 1st sergeant was not at all popular. H was an old country boy from Tennessee named Durett. He as a little too GI for most of us. As the story goes, a couple of the guys crapped in his footlocker and suspended the locker on a rope from a second story window. I don't know if the story is entirely true, but I do recall seeing the footlocker hanging from that window.

CHAPTER FOUR

My First Taste of Combat

My First Taste of Combat

On July 12th [1944, in France] we moved into an area where foxholes had already been dug. About two hours before dark, our squad leader, Corporal Duck, came by our foxhole. Duck weighed about 140 pounds and was about my size. He told Nestor and me that a German tank attack was expected. Nestor and I knew that the Germans had two types of main battle tanks, the Panther and the Tiger. Both types had been used in our area. They were huge, noisy, heavily armored and hard to knock out.

Duck told us to stay in our holes until a tank got so close that its machine gun would be ineffective due to its vertical movement restrictions. Duck also told us that if we got the chance, we should stick our mortar barrel in the tank tread, causing the tank to stall. he said that the tank would then be unable to move and would become a sitting duck for our anti-tank guns.

Duck asked us if we were scared, and we said yes. He said, "Good. That means you are normal. All it takes to get out of here and get back home are three things: A little bit of guts, a little bit of initiative, and a whole lot of that NEW TESTAMENT!"

Any man who says he is not afraid in combat is a liar. Fear, however, does not keep one from being a good soldier. This is where those long months of training come in. Discipline was the most important thing they taught us. When a person first goes into combat, he is primarily concerned with his own safety and it isn't until he has spent some time "getting his feet wet" under fire that he adapts to the situation, starts to think about accomplishing the mission, and becomes an effective fighting soldier.

While Nestor and I were in the foxhole that night, we received a lot of incoming artillery fire. Typically, a foxhole is dug a couple of feet deep, just big enough for two men. Th dirt that is removed is placed around the edge or rim of the hole, giving the occupants an extra foot or so of protective cover. This dirt is called the"parapet."

Most of the incoming artillery fire we experienced was from German 88-millimeter long-barreled canon, or simply "German 88's" Incoming artillery from the Germans was referred to as "incoming mail." Likewise our artillery fire was "outgoing mail." When artillery shells are coming in, you can get a good bearing on their direction and location by the sound they make.

During the shelling that night, one round seemed destined for our foxhole. It hit close enough to throw loose dirt on us, but t turned out to be a dud. Nestor and I thought at that moment that we owed our lives to some Polish prisoner or forced French laborer for sabotaging that shell at the German factory.

That night, Nestor and I discussed our possible fates. There was that ever-present possibility of being killed. Being wounded or making it through combat without incident were also possibilities. I remarked to Nestor that if we were to be wounded, the shoulder or thigh would be less life-threatening. Little did I know that the events of the next 24 hours would later make me wonder if I had ESP!

Luckily, the tanks never appeared the rest of that night. Years afterward, I found out why. According to the history of the 12th Infantry Regiment, it seems that one soldier in our regiment, a Private Weinschrott, immediately advanced on a German tank column with his rifle and attached rocket launcher. "While exposed to artillery, tank and small arms fire, he found a point of vantage from which to fire his weapon. The enemy tanks launched an attacked and moved in the direction of Weinschrott's platoon. He exposed himself to heavy fire in order to operate his weapon, and succeeded in knocking out the lead tank with his first rocket. The remaining tanks withdrew. The enemy then increased the intensity of their fire, but Private Weinschrott remained in his precarious position throughout the night, ready for further action; but the second German attack failed to materialize."

The next morning, July 13, 1944, our regiment was designated as one of two assault regiments of the 4th Division. After about 30 minutes of walking to our jumping off point, we reached an area where the fields were surrounded by hedgerows. At that point, we were just a short distance south of the town of Saintenay in northwest France, about 10-12 miles from St. Lo.

The hedgerows were long thickets of trees, bushes and undergrowth that formed natural fences between large areas of open pastureland and fields. It was in one of these fields that we smelled something dead, and thought it might be a human body. A little further ahead, we saw a dead Holstein cow, which probably had been killed by an exploding artillery shell or stray gunfire. From the look of it, it had been dead for several days, as it was extremely bloated. I'll never forget the smell -- decaying animal flesh and gunpowder. It stayed with me for the longest time.

On the way to our destination, I saw my first dead American soldier. I walked within a foot or so of his body. The only visible injury he had was a small hole in the back of his field jacket. I can only guess th the had been hit by a sniper's bullet. The stillness of his body got to me. I felt for him and I knew that there were those at home who would eventually get the news about him. My greatest fear was that Mom would get a telegram telling her that the same thing had happened to me.

The Allies were usually very efficient about collecting and buying our dead from the battlefield. Great pains were taken to collect the dog tags of our dead soldiers and to account for their loss. Each of us had two dog tags on a chain around his neck. It was the job of the Graves Registration Unit to recover and bury the bodies.

That morning, after reaching our destination within yards of the enemy, we were soon pinned down by German small arms fire. I remember trying to keep as close to the ground as possible and using the steel mortar base plate I carried as a shield for my head. I could smell the odor of burnt wood as German slugs tore into the hedgerows nearby. Nestor was directly behind me.

The enemy resistance was very heavy in the hedgerow country and the Germans were dug in very well. In order to dislodge them from the hedgerows, we needed our artillery to open up on them. Due to their close proximity to us, we needed to pull back just before our artillery fire started.

Because they may be miles away, and in order to be able to hit what they're shooting at, artillery batteries needed someone located within visual range of the target. That is, they needed someone to tell the shooters where their shots are falling. The appropriate corrections or adjustments are made, and the batteries shoot again. This process continues until the shots are "walked in" on the target. The lucky (or unlucky) fellow who calls the shots is known as an artillery observer or forward artillery controller.

After an undetermined amount of time, we were ordered to pull back. The artillery observer called for American artillery to be dropped on our position in 12 minutes. today, 65 years later, it is hard to imagine that I was ever in such a situation. It would have helped greatly to know then that I would be writing about it now.

CHAPTER FIVE

Wounded in Hedgerow Country

Wounded in Hedgerow Country

Our CO gave the order to fall back. As we started, Nestor was now ahead of me. After he passed an opening in the hedgerows, and while I was crossing it, he turned and screamed at me, "Olie, machine gun!" I had just started to dive to the ground when a German mortar shell exploded somewhere behind me. Unlike artillery, incoming mortars make no noise, or at least it is not audible since it is coming almost straight down. The concussion of the exploding shell tossed me about three or four feet. A piece of shrapnel from the mortar round struck me on the back of my left shoulder. From the size of the wound, the piece of shrapnel that hit me must have been about three inches long. Another piece of shrapnel apparently ricocheted off the mortar tube I was carrying on a sling on my right shoulder. The tube swung forward as I was on my way to the ground and the shrapnel entered the fron of my left thigh. I recall feeling as if I had had a hole blown through me. It felt like someone had hit me across the back with a baseball bat. I took a deep breath and realized that it was the concussion that made me feel that way. Luckily, the shrapnel that struck me in the back of my shoulder was a glancing blow, which made a hole about three or four inches across.

I owe my life to my best buddy, Nestor, for warning me of the German machine gun that day. I have replayed the incident in my mind thousands of times over th years since then. The fact that I was in the motion of going to the ground saved me from what could have been a hit on my spine or into a lung, either of which would have been fatal. Thank God Nestor made it all the way through the war without being wounded or killed.

Immediately after the explosion, a lieutenant came running by my position. I told him that I had been hit. He said, "I know. Keep moving and look for a medic." I realized than that I had taken the piece of shrapnel in the leg, although I cold walk with little difficulty. I must have found a medic, or one found me, because the next thing I remember was being at the battalion aid station, several hundred feet back from the fighting. the medics gave m a shot of morphine for shock, and they treated my shoulder with sulfa powder and a bandage.

At the aid station, I was placed on a stretcher and traveled by Jeep to a field hospital, similar to the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) units in Korea. I found out later that the mortar shell, which had wounded me, had killed one soldier and had wounded on other. Upon arriving at the evacuation hospital, a big buck sergeant helped move me. He asked, "Hey, Sweetheart, how you doing?" When he saw the 4th Division shoulder patch on my uniform, he said, "You did a lot better than one of your other 4th Division buddies." I became scared because I thought he was talking about Nestor, and that Nestor must have been killed or seriously wounded. The sergeant then told me that Brigadier General Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt, Jr. had died during the night from a heart attack, just a few feet from where we were.

General Roosevelt had been assigned to the 4th Division as an "extra general." He was the only general to land in France on D-Day, and he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for rallying his troops, who had landed a mile off-course. The "snafu" (Situation Normal - All Fouled Up) was a blessing in disguise, because their actual landing zone was not as heavily defended by the Germans as was the intended landing area. After the landing, General Roosevelt's troops were scattered and in disarray. He told them, "Gentlemen, the war starts here?" He was a "Gi's general," often opting to be with his troops on the very front lines. His loss was felt by the whole 4th Division.

Prior to my surgery, I sneaked a look at my x-rays, which were hanging at the foot of my cot. The film showed nine small pieces of shrapnel, each about the size of a pea, in the back of my left shoulder. The next thing I remember was going into surgery around midnight. My wound was about the size of a softball and the surgery involved pulling the skin together. This type of surgery hastened my recovery.

The general anesthetic, sodium pentothal, was fairly new and still in the experimental stage. I didn't come around and regain consciousness from surgery until the next afternoon. I felt very groggy and I needed badly to urinate -- hard to do when you're flat on your back. A medic told me that if I could stand, it would be a lot easier. He also told me that if I was unable to void, a catheter would have to e inserted. I didn't like that idea, so I went outside the tent and very thankfully let go.

The surgeon had removed all nine pieces of shrapnel, but missed the piece in my left leg. I still carry hat one. In the 65 years since then it has moved about four inches from where it entered my leg.

We were moved on stretchers, taken down to the beach, and loaded onto an amphibious Navy ship called an LST (Landing Ship - Tank). This was early evening. We crossed the channel during the night, and arrived the next morning in Bournemouth, England. As we arrived, there was a ship nearby loaded with nurses, who were soon to cross the channel for France. Some of them waved at us, some were crying and some even saluted. The sight of us was their first inkling of what was in store for them.

CHAPTER EIGHT

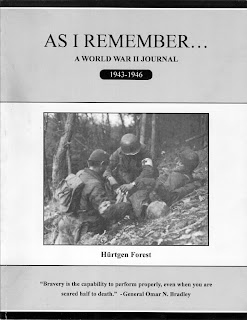

The Hurtgen Forest

The Hurtgen Forest

[From near Holzheim, Belgium] We loaded onto 2 ½ ton trucks and rode north for about six hours. I found out later from division records that the six-hour trip spanned only 30 miles. We arrived near the town of Zweifall, Germany before daylight in an area of approximately 50 square miles along he east side of the Belgian-German border called the Hurtgen Forest. The towns of Hurtgen, Iffle and Germeter, Germany lay nearby. At that time our company headcount was about 170 men. We had suffered a low number of casualties the previous two weeks and many who had been wounded had rejoined the unit. We were actually over-strength for a change.

After reaching our destination at about 4:00 am, we de-trucked. It was still dark and it was difficult to organize. I recall Sergeant Parker asking, "Where's Olie?" Sergeant Parker was like an old mother hen, checking on her young.

We were to take up the positions of the 28th Division's 109th Regiment. The 12th Regiment then came under the command of the 28th Division. We were told to leave our mortars behind and take possession of those of the 109th Regiment.

On the way to our new positions, we passed members of the109th Regiment coming back to the rear area. I spoke to one of them and he just stared through me. These guys had had the hell beaten out of them.

As I write this journal, I learned most of what I know now about my time with the 4th Infantry Division from the histories of the units involved. I certainly didn't know this much at the time. It might surprise the general public that the "grunts" and other enlisted men in combat were grossly uninformed about their location and purpose. The lower in the food chain you were, the less informed you were. I don't think they wanted to keep us in the dark on purpose, but information security was vital, in case any of us was captured. We didn't have "a need to know" the big picture. Orders were passed down from the top, and by the time the got down to the foot soldier, all he was told was his immediate objective. In Normandy, our strategic objective was Saint Lo, France. In the Hurtgen Forest our strategic objective was Cologne, Germany.

The Supreme Allied Command chose the most direct route (through Hurtgen Forest) on its intended path to control of the Roar and Rhine river dams. The generals were afraid that the retreating Germans would destroy the dams, flooding the river valleys and delaying the Allied advance into Germany. But the strategy of entering the Hurtgen forest was flawed, because it enabled the smaller and retreating German Army to gain the tactical advantage afforded by the terrain and by their well dug-in positions.

The Germans wanted to maintain control of Hurtgen Forest, for beyond it a few miles to the northeast lay the "autobahn," a modern highway to Cologne. The Germans knew that the loss of Hurtgen Forest would pave the way for the eventual fall of Cologne to the Allies.

The battle in Hurtgen Forest would later be described in Life Magazine as one fo the bloodiest battles of WWII. The magazine devoted several pages to pictures and an article, "Hurtgen Death Factory." General Matthew Ridgeway of the 82nd Airborne Division and other respected generals later said that Hurtgen Forest was one of the most costly and ill-advised decisions of the entire war. Even a former German general spoke of the American battle strategy in a belittling manner. As it turned out, the Allies needed only to have diverted their attack to the south, bypassing the Forest, to avoid the costly loss of American lives. The 9th, 28th and 4th Divisions suffered the loss of from 60% to 70% of their men, all to satisfy the ego of "Lightning Jo" collins, commander of VII Corps. But Generals Eisenhower and Bradley also signed off on the strategy. During the battle from September 16th 1944 to February 10th 1945, the U.S. Army sustained 33,000 casualties, a figure later questioned by researchers. Some put the actual figure at over 50,000.

Once in position inside the Forest, we were subject to intense shelling day and night by German artillery. Prior to the arrival of American troops, the Germans had entrenched themselves and had zeroed in their artillery on areas where they anticipated we would be. The deadly effectiveness of their artillery was improved by "tree bursts." When a German shell detonated by hitting the treetops, a would spray shrapnel and pieces of wood over a wider area than if it had hit the ground. Even a foxhole offered little protection. "Hugging a tree" afforded more protection than diving into a foxhole.

After a short time in the Forest, casualties robbed us of some of our non-commissioned officers. It was here that Sergeant Parker "tot it." He was a great non-com who was always concerned for the safety of his men. So many of our non-commissioned officers and junior commissioned officers, "tot it" that soon Nestor and I were offered promotions to corporal and squad leader, but we both declined. An ammo bearer, John McFall, accepted the promotion. He was killed a couple of days later.

The most effective weapon that our division possessed, given the terrain and heavy forestation, was the 81-millimeter mortar, used by the heavy weapons company from Battalion. The 60-millimeter mortars, such as the one Nestor and I operated, were completely ineffective. This is because the 60mm had a limited range and was hampered by the overgrowth of the trees. The 60mm's were phased out in favor of bazookas, which were much more accurate.

I did not see any German soldiers while we were in Hurtgen Forest, but their artillery fire was unceasing and had a devastating psychological effect on us. It was disheartening, frustrating and fatiguing to be shelled day and night over the course of many days and nights without the opportunity to fight back or to escape the unending explosions.

One time, Nestor, I and the rest of my platoon took refuge in a dugout located near a saw mill. The Germans had dug it and had covered it with heavy timbers during their construction of Hitler's vaunted Siegfried Line, a supposedly impenetrable defensive wall. As I recall, it was about 20 feet by 20 feet and about eight feet deep.

During the day, the Forest's trees blocked out most of the light. As a result, there was darkness and little, if any color. Inside the dugout was complete darkness except for an occasional match or a lit can of Sterno that we used for heating our rations. This constant pass added to the sense of hopelessness.

There was no sunlight, and most of the time it either rained or snowed. The ground was muddy all of the time and you couldn't get dry or warm. We were always wet, always cold, and thanks to the German artillery, constantly awake or semi-conscious. Nearly all of us suffered from frostbite, hypothermia and trench foot.

Sleep deprivation and exhaustion soon led to many "no-battle" casualties. For example, my squad leader, Corporal Elliott accidentally discharge his M-1 rifle when a piece of wire became entangled in his legging and his rifle's trigger. The bullet practically tore off his left arm at just below his elbow. I remember our platoon leader, Lieutenant Graham, telling him that if anyone questioned whether his wound was an accident or self-inflicted, to contact him. Luckily, no one else was injured during that incident.

You couldn't see the enemy, you couldn't kill the enemy, you couldn't advance to another location, and you couldn't retreat. You just had to stay put, take a pasting, and watch your buddies be killed or wounded.

Many of our casualties in Hurtgen Forest were from "combat exhaustion." This condition is similar in all people, but the outward symptoms can vary from man t man. Some developed very strange behavior. Some would ignore their training or simply forget things and would unnecessarily expose themselves to danger. Others simply reacted slowly to danger, becoming almost like robots.

Combat exhaustion has nothing whatsoever to do with fear. It is the mind's eventual reaction to the prolonged and sustained combat stress with no decompression or detoxification. In fact, the most commonly exhibited symptom of combat exhaustion is an irrational lack of fear, and an inability or unwillingness to recognize threats to one's own personal safety. In any case, once a man became afflicted with combat exhaustion, he was of no value as a combat soldier.

There was a feeling of despair among the members of my platoon. I really wonder if anyone there thought there was much chance of our getting out of the Forest alive. I, for one, didn't think so. It seemed that everything that had happened and everything that was about to happen was grim.

© Jack E. Oliver 2010

Commentary:

These are just brief, incomplete glimpses into the World War II service of one of the millions who served. Jack Oliver and his buddy, Nestor, were pinned down in Hurtgen Forest by the constant artillery fire when one of the shells hit a tree maybe 20 feet above his head. Their "shell shock," what we called post traumatic stress disorder today, was very real. They were both sent to the rear for rest. But the effects of Hurtgen Forest stayed with "Olie" for a lifetime. The complete story is available in the BCHS library.

No comments:

Post a Comment